What does the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor mean for Mongolia?

Guest contribution by Connor Judge. Connor is a PhD Candidate at SOAS, University of London specializing in Chinese history and China-Mongolia relations. He holds an MA in International Relations from the University of Nottingham, Ningbo China, where his research focused on Eurasian regionalism and Mongolia’s economic development. His research output is supported by the Wolfson Foundation.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the text belong solely to the author.

Source: https://www.fort-russ.com/2017/08/russia-mongolia-china-economic-corridor/

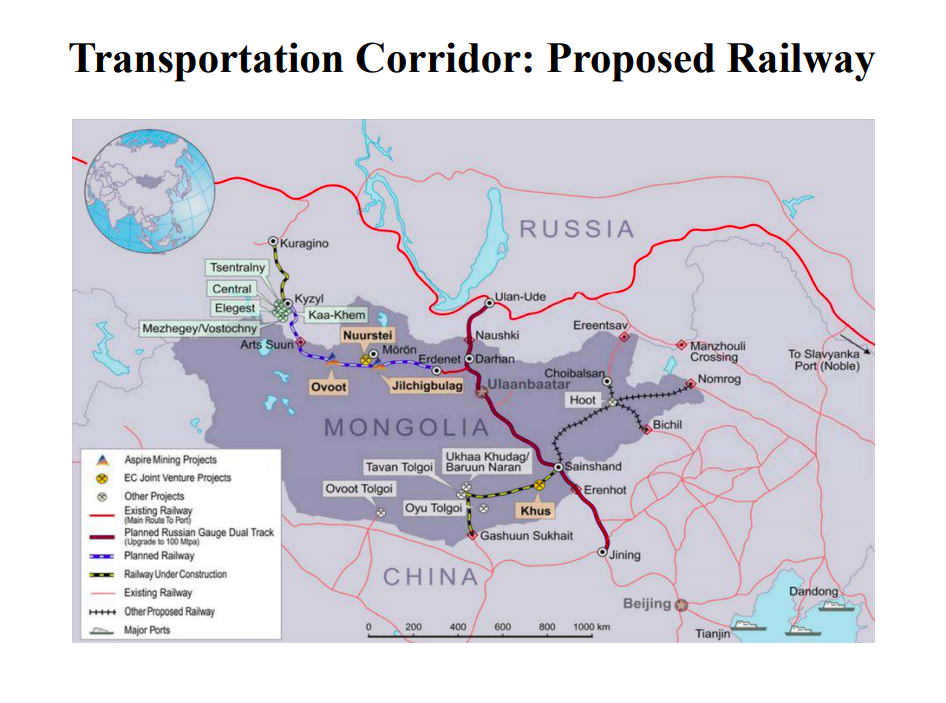

2019 marks 70 years of diplomatic relations between China and Mongolia. The two countries are eager to use the opportunity to strengthen relations and lay out a blueprint for future cooperation. It was in this context that Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Mongolia in late August. During the visit, it was agreed that both sides would accelerate construction of the flagship China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor (CMREC), one of the key corridors under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

CMREC central route

Source: Source: https://www.iru.org/where-we-work/iru-in-asia-pacific/China-Russia-trade-corridor-pilot-caravan

Central CMREC route already in use

The central CMREC route (also known as the “Prairie Road” (Талын зам\草原之路) “starts” at the port of Tianjin, China and heads northwest before entering Mongolia at the Erlianhaote border crossing. In practice however, Siberian and Mongolian resources are exported out of Tianjin. The route then heads through Mongolia before entering Russia along the trans-Siberian express at Ulan Ude. For North East China’s provincial powerhouses, this primary route represents the shortest path to Europe; and Mongolia is keen to position itself as the pivotal logistics hub.

Container trains have already traversed the new corridor. The Mongolian Vector (Mongolia-Brest, Belarus) and Zhengzhou-Hamburg (China-Mongolia-Germany) trains have already been running successfully along the route and are providing European firms with potential for both Mongolian and Chinese market access; as well as vice-versa.

Other CMREC routes face delays

Beyond this central route, alternative ideas have been put forward for CMREC, but progress has been slow.

Other proposed CMREC routes

Source: Institute for Strategic Studies, National Security Council of Mongolia

● Tavan Tolgoi Rail Project: Seeks to link Mongolia's giant Tavan Tolgoi coal mine to the Chinese border. $200 million has already been invested. However, funding for the route, contributed thus far by Shenhua Group and Sumitomo Corporation, falls short by $800 million.

● The Mongolian government was also enthusiastic about integrating a rail route stretching from Choilbasan to the town of Ereentsav near the eastern Russia-Mongolia border within CMREC, but China has been less receptive to this.

● A proposed Sainshand-Ereentsav, Nomrog, Bichil crossrail is also seeking funding from the Silk Road Fund (SRF) and Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

● The construction of an international UHV electric transmission “super grid” along CMREC routes and existing grid upgrades are also being considered at multilateral dialogues.

Mongolia is pushing China and Russia to turn words into action

Financing, rail gauge incompatibility, customs, environmental and broader conceptual issues continue to be roadblocks for CMREC and the proposed projects mentioned above. Mongolia nonetheless is keen to resolve these issues. As a result, Mongolia is an active and vocal BRI partner, while simultaneously pursuing a self-promotion drive. For example, former Mongolian Transport Minister Jadamba attended a plenary Transport and Logistics in Eurasia conference in Moscow in December 2017 in which he reiterated Mongolia’s pivotal role as the “shortest” path between Europe and Asia, while also emphasizing Mongolia’s desire to seek third-party partners for CMREC and mineral export financing.

More recently in June 2018, the Mongolian President Khaltmaagiin Battulga also spoke at the Mongolia-Russia Economic Forum where he promoted the Altanbulag FTZ at the northern extreme of the central route, efforts to significantly increase trade turnover with Russia by 2020 and establishing of an FTA with the Eurasian Economic Union.

In the same speech, however, Battulga stressed that CMREC “remains no more than a dialogue today” and that Mongolia expects deeper reciprocation of its “robust implementation” of the project. Battulga continues to seek more buy-in from Russian and Chinese partners, and at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in June 2018, the three CMREC country leaders arrived at a further consensus on expanding CMREC, but also agreed that Mongolia should engage more with the SCO. Subsequently, Mongolia participated alongside China in the Vostok games, Russia’s largest war games since 1981.

Hedging bets?

Faced with challenging realities of landlockedness, Mongolian officials recognize that rail and road infrastructure remain key to the economy’s sustained growth and development (following a lamentable $5.5 billion IMF bailout package in 2017). As such, Mongolia recognizes that, if implemented well, CMREC could be a game changer and hence is pressing for it with vigour.

At the same time, Mongolia is wary of economic over-reliance on China and the asymmetric implications that may come with CMREC. Already, around 80% of Mongolia’s export volume goes to China (primarily copper, coal and gold). This explains why Mongolia is seeking additional international investment partners and political allies, including agreeing to expand a comprehensive partnership with the US. Additionally, despite Chinese interest, the Mongolian government continues to lease the “backbone” of the Mongolian mining industry, the South Gobi Oyu Tolgoi mine, to Canadian Ivanhoe Mines and multinational Rio Tinto.

Mongolian interests

Nevertheless, the overall trend for Mongolia’s economic engagement with China remains positive. The Mongolian side likewise appears willing and invested in CMREC and stakeholders can safely assume this attitude will persist. For Mongolia, CMREC embodies fervent hopes for sustainable regional collaboration and development.